{On April 5, 2013, we will celebrate the 15th Anniversary of the First Friday Book Synopsis, and begin our 16th year. During March, I will post a blog post per day remembering key insights from some of the books I have presented over the 15 years of the First Friday Book Synopsis. We have met every first Friday of every month since April, 1998 (except for a couple of weather –related cancellations). These posts will focus only on books I have presented. My colleague, Karl Krayer, also presented his synopses of business books at each of these gatherings. I am going in chronological order, from April, 1998, forward. The fastest way to check on these posts will be at Randy’s blog entries — though there will be some additional blog posts interspersed among these 30.}

Post #26 of 30

——————–

Synopsis presented March, 2010

The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right by Atul Gawande. (Metropolitan Books. 2009).

Yesterday, I wrote about Switch: How To Change Things When Change is Hard by Chip Heath & Dan Heath, Here is what they wrote in that book about checklists (referring to Atul Gawande’s insight):

Checklists provide insurance against overconfidence… Checklists make big screwups less likely.

There is great value in “humble checklists.”

Question: how many things fall through the cracks at your work? In your work?

Atul Gawande was tasked with quite a challenge. He had to help reduce deaths in hospitals across the world, especially in places where resources were scarce. As head of the Surgical Task Force for the World Health Organization, he saw stacks of reports, copies of materials that had been distributed… and very little progress. He finally came up with the “Surgical Check List.” It worked.

Dr. Gawande is kind of a marvel. He is a surgeon; he teaches surgery at Harvard; he headed the WHO Surgical Task Force; he is a journalist for The New Yorker; he has authored important books. And, he is a MacArthur Fellow (commonly referred to as “The Genius Grant”).

But it is his call for the “humble checklist” that includes him in this series of 30 books.

He begins his book with the story of the man who nearly died at the emergency room because he had a “knife” sticking out of him. When they pulled the “knife” out… it was a bayonet, not a knife. A rather big! “misdiagnose.” From the book:

No one remembered to ask the patient of the emergency medical technician what the weapon was. “Your mind doesn’t think of a bayonet in San Francisco.”

Here’s what he found out. (This is a profound paragraph!):

We have just two reasons that we may fail.

The first is ignorance – we may err because science has given us only a partial understanding of the world and how it works. There are skyscrapers we do not yet know how to build, snowstorms we cannot predict, heart attacks we still haven’t learned how to stop. The second type of failure the philosophers call ineptitude – because in these instances the knowledge exists, yet we fail to apply it correctly. This is the skyscraper that is built wrong and collapses, the snowstorm whose signs the meteorologist just plain missed, the stab wound from a weapon the doctors forgot to ask about.

For nearly all of history, people’s lives have been governed primarily by ignorance.

The very big little errors add up, and are so very costly:

At least 30 percent of patients with stroke receive incomplete or inappropriate care from their doctors, as do 45 percent of patients with asthma and 60 percent of patients with pneumonia. Getting the steps right is proving brutally hard, even if you know them. (emphasis added).

And such failures anger us all.

Failures of ignorance we can forgive. If the knowledge of the best thing to do in a given situation does not exist, we are happy to have people simply make their best effort. But if the knowledge exists and is not applied correctly, it is difficult not to be infuriated. (emphasis added).

What Dr. Gawande found was that the greater the complexity, the more necessary some simple “checks,” some approach to remember to get the steps right:

Every day there is more and more to manage and get right and learn. And defeat under conditions of complexity occurs far more often despite great effort rather than from a lack of it.

It is not clear how we could produce substantially more expertise than we already have. Yet our failures remain frequent. They persist despite remarkable individual ability.

(our) know-how is often unmanageable. Avoidable failures are common and persistent, not to mention demoralizing and frustrating, across many fields – from medicine to finance, business to government. And the reason is increasingly evident: the volume and complexity of what we know has exceeded our individual ability to deliver its benefits correctly, safely, or reliably. Knowledge has both saved us and burdened us.

That means we need a different strategy for overcoming failure…

and

To save this one child, scores of people had to carry out thousands of steps correctly…

Medicine has become the art of managing extreme complexity – and a test of whether such complexity can, in fact, be humanly mastered.

The book is about checklists for surgeons, but also about the history of checklists, and checklists and their value in many different arenas: construction projects, kitchens with a team of preparers… The checklist is useful in practically every arena.

Pilots had to come up with a checklist, because planes became ever more complex – “too much airplane for one pilot to fly.” (And, it was the use of the checklist that helped Chesley Sullenberger successfully land that plane in the Hudson River a while back). The pilot’s checklist was born by necessity after a fatal and costly crash.

(1935 – re. the Boeing Model 229, the B-17, the “Flying Fortress”) — The test pilots made their list simple, brief, and to the point – short enough to fit on an index card, with step-by-step checks for takeoff, flight, landing, and taxiing. It had the kind of stuff that all pilots know to do… With the checklist in hand, the pilots went on to fly the Model 229 a total of 1.8 million miles without one accident.

Read these “arguments” for the checklist:

Checklists remind us of the minimum necessary steps and make them explicit.

Checklists help with memory recall and clearly set out the minimum necessary steps in a process.

In one hospital, the checklist had prevented forty-three infections and eight deaths and saved two million dollars in costs.

Checklists provide a kind of cognitive net. They catch mental flaws inherent in all of us – flaws of memory and attention and thoroughness. And because they do, they raise wide, unexpected possibilities.

Checklists can provide protection against elementary errors.

You want people to get the stupid stuff right. Yet you also want to leave room for craft and judgment and the ability to respond to unexpected difficulties that arise along the way. The value of checklists for simple problems seems self-evident. But can they help avert failure when the problems combine everything from the simple to the complex?

And why do we all need checklists?

Discipline is hard – harder than trustworthiness and skill and perhaps even than selflessness. We are by nature flawed and inconstant creatures. We can’t even keep from snacking between meals. We are not built for discipline. We are built for novelty and excitement, not for careful attention to detail. Discipline is something we have to work at.

He ends his book with a chapter about a life that was saved because of an error he made in surgery. If the team had not followed the checklist, it would have resulted in the death of his patient. This is a life-and-death tool, and for most of us, a success-instead-of-failure tool.

I have yet to go through a week in surgery without the checklist’s leading us to catch something we would have missed.

Here are key elements about the checklist manifesto, from my handout for my book synopsis:

• two main problems: (you might add a third, at times – sheer exhaustion)

#1 – the fallibility of human memory and attention (especially for mundane and routine matters)

#2 – people can lull themselves into skipping steps (this is “never a problem”)• The First Try

• great success from free soap for the poorest of the poor

• the checklist printed on a “tent” over the scalpel for the operating room

• (an aside: remember the power of “convenience”)

• the checklist requires that the team talk to one another – at least for one minute – to become a “team” before surgery (a “team huddle”)

• “people who don’t know one another’s names don’t work together nearly as well as those who do.”• The Checklist Factory

• Boeing – checklist(s) born out of necessity

• Bad checklists are: vague; imprecise; too long; hard to use; impractical;

(made by desk-jockeys)

• Good checklists are: precise; efficient, to the point easy to use; above all, practical…

• Two kinds of checklists: DO-CONFIRM; and READ-DO

• Checklists are best with between 5-9 items

• fit on one page; free of clutter, and unnecessary colors

• a checklist has to be tested in the real world! (“first drafts always fall apart.”)

• checklists are not comprehensive how-to guides: “they are “quick and simple tools aimed to buttress the skills of expert professionals”And, an aside (in the chapter about Sullenberger and the landing in the Hudson River):

• The code for all professions/all professionals:

1) An expectation of selflessness

2) An expectation of skill

3) An expectation of trustworthiness

4) An expectation of discipline

After the surgical checklist was tested, here was the finding:

• after the trial, 80 % approved, but 20% found it not easy to use, thought it took too long, felt it had not improved the quality of care: BUT – “If you were having an operation, would you want the checklist to be used?” – 93% said yes.

A personal note: there are “natural” checklist makers, and then there are the rest of us. My wife is a natural. Her father, advanced in years and diabetic, is living with us, and we need to take his blood sugar, and inject his insulin, four times every day. There are times when my wife has been out of town, and I have had the task checking and injecting. How do I remember each of the steps? My wife created a checklist, with a table for me to follow, and slots for me to record each check. There is nothing left to chance, or to faulty memory. His life depends on us getting it right. This book explains why getting this right is so very, very important. My wife’s checklist is not a nice idea – it is a necessity.

This book may be as important as any on this list. Do you have things fall through the cracks in your work life? At your work by others? Read, and follow, this book, and that might happen less often…

——————–

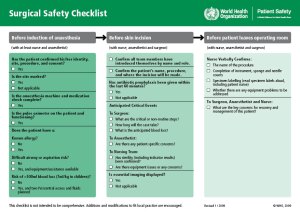

Here is the official, adopted surgical checklist. Take a look.

And here is a 4 1/2 minute video (from the TV show ER) demonstrating the value of the checklist. Fictional, but very real.

And, for further reading:

Read these articles by Atul Gawande:

The Checklist: If something so simple can transform intensive care, what else can it do?

and

A Lifesaving Checklist.

And, here is Dr. Gawande’s web site, with many of his articles.

You can purchase many of our synopses, with our comprehensive handouts, and audio recordings of our presentations, at our companion site 15minutebusinessbooks.com. The recordings may not be studio quality, but they are understandable, usable recordings, to help you learn.

(And though the handouts are simple Word documents, in the last couple of years we have “upgraded” the look of our handouts to a graphically designed format).

We have clients who play these recordings for small groups. They distribute the handouts, listen to the recordings together, and then have a discussion that is always some form of a “what do we have to learn, what can we do with this?” conversation. Give it a try.