By Linda Fisher Thornton

After teaching for more than 20 years, I was surprised last week with the Itkowitz Family Distinguished Adjunct Faculty Award by the University of Richmond School of Professional and Continuing Studies. This is especially meaningful recognition for me, since I had “learned through” the process of completely redesigning my Applied Ethics course as an online course and changed my teaching approach during the pandemic. This course redesign was an arduous process, and one that stretched me to become a better professor and a better person.

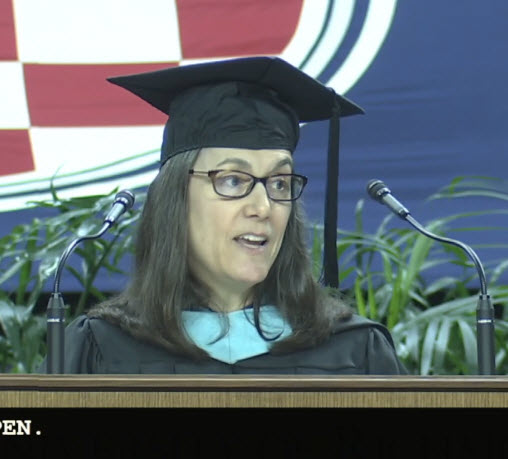

This prestigious teaching award came with the wonderful opportunity to speak at Commencement on May 7th, sharing wisdom with the graduates. In celebration of this award, I am reflecting on my teaching over the past 22 years, and sharing five unexpected things I’ve learned along the way in the hope they may inspire you as a teacher or as a lifelong learner.

5 Unexpected Teaching Insights

1. Homework causes painful tradeoffs.

In their busy lives, every time students do homework, they do it instead of something they’d rather be doing. It’s instead of time with family or friends, instead of working and getting paid, instead of sleeping, or instead of participating in social events. Every assignment should be meaningful enough that it’s worth those tradeoffs, and it should be manageable enough that students can succeed without undue stress. Life is stressful enough; Learning shouldn’t be.

We should always ask ourselves, “Is the outcome of that activity going to be worth the painful tradeoffs for the student?” While some teachers treat homework as “adding rigor,” unless it is carefully designed it may just be holding students’ time hostage. Holding students’ time hostage would include things like having learners repeat things they’ve already done or asking them to struggle through a task with poor instructions or preparation. Homework should be carefully used to stretch students, and it should be made as pleasant as possible while stretching them. It’s fine to have to think hard to complete an assignment when all of the foundational learning has been provided, but not fine to stretch students without the proper support.

2. Testing is a form of judgment.

The way we test has a profound impact on student well-being. Testing can be a demotivator and generate harmful stress if it’s done in the spirit of “catching students doing it wrong.” Asking students to memorize and regurgitate facts does not prepare them to handle their challenges in the real world. The whole point of teaching is to ignite the love of learning and guide students to higher levels of understanding and capability. Extremely difficult tests on which everyone gets a poor grade are not then a reflection of the effort students have put into the learning, they are a reflection of the lack of effort the teacher has put into the learning process and the test design.

I like to think of testing as a way to review the material and to make sure students retained the key learning from the course. In other words, I treat testing as part of the learning instead of just as a judgment about what they do or do not know. Test anxiety is real, and some students don’t do well on tests because they are under great stress to do well. We can mitigate this stress by treating tests as part of the learning, and balancing test grades with many other non-test grades throughout the semester so tests are not “make all, break all” to the semester grade. A course grading schema with 70% or more of the final grade based on tests and quizzes seems to be designed more to intimidate than to ignite the love of learning. And testing for “right answers” is not productive when what we really want is higher level thinking.

3. Attendance is not learning.

Throughout my time teaching working adults, I have struggled with the attendance issue. Should students lose valuable points for missing one class if they have proven they know the material? Shouldn’t their grade be lower than the grades of the students who showed up every time? During the pandemic, I realized just how little control we all have over our lives. Whether or not a student could attend class in a time of COVID depended on whether or not they had been diagnosed with COVID and were not allowed to come to class, or were exposed to someone who had COVID and were isolating, or had symptoms and did not yet have test results back, or had to work and couldn’t get out of it, or were caring for a sick family member, or had lost child care, or were in a car accident, or were in the hospital, or were dealing with a multitude of other challenges.

Weary from the constant process of marking off points for attendance, I recreated my course so that if students missed any live sessions, they could get the learning online on their own time and keep up with the class. Doing this, I realized, also solved for many of the emergencies I had faced in teaching over the years, including tornado warning evacuations, black ice, snowstorms, hurricanes, and other disruptive events none of us could control that cancelled classes and interrupted the flow of learning. I learned in this process that attendance does not necessarily equate to learning and is not always controllable, and that flexibility in how and when students can learn benefits everyone.

4. Rigor can’t travel alone.

Some teachers think that rigor is the ultimate proof of great teaching, but that is definitely not the way we should be thinking about rigor. Yes, we need to stretch students to think in new ways, apply what they’re learning, and show that they have mastered it. The problem is that rigor can’t travel alone. Rigor without support is very much like hazing, akin to “I’m going to put you in this difficult situation and expect you to get yourself out of it with no help.” That is not what teaching is supposed to be about. Good teaching is a process of explaining, guiding, giving feedback, inspiring, and coaching to a higher level.

Some professors equate a higher level of rigor to doing good teaching, but when they do, they’re missing a very important part of the equation. Rigor has to travel with care and support. Alone, rigor is negative and stress inducing, and stress quite efficiently dampens students’ ability to learn. With the addition of care and support, though, rigor can be challenging, engaging, interesting and motivating.

5. Simplicity on the other side of complexity is the gold standard.

As teachers, we should do the hard work to synthesize and clarify and organize the learning material and concepts so that students can learn it as easily as possible. That does not mean “dumbing it down.” On the contrary, it means taking the time to slog through the complex topic to reach clarity and coherence so students don’t have to individually slog through trying to figure out what it means. Having done that, we can take their learning much farther, and focus more time on higher level skill development. In other words, while it may seem counterintuitive, they’ll learn more, but the learning process itself will be easier.

Teaching is the process of bringing out the best in every student. I have learned over the years that to accomplish that requires those of us who teach to do the work to bring out the best in ourselves.

Unleash the Positive Power of Ethical Leadership

© 2022 Leading in Context LLC